With a weekend ceasefire supposedly on track, the next step is to figure out when the on-again-off-again Syrian peace talks will resume. United Nations special envoy Steffan De Mistura is set make an announcement tomorrow, though exactly which if any of the parties actually doing the fighting will agree to sit down for these talks remains as uncertain as ever.

In fact most everything about Syria right now — which factions will sign on to the ceasefire, which ones will actually honor it, whether the Russians will game the terms of ceasefire to continue to bomb forces opposed to the Assad regime, whether Turkey will ignore the ceasefire and continue bombing Kurdish fighters, etc., etc., etc. — is pretty uncertain.

So it stands to reason that the United States is floating the possibility of a “Plan B” if the ceasefire and peace talks that constitute “Plan A” fail to bear fruit. Unfortunately, the alternative that Secretary of State John Kerry is raising is partition, redrawing the borders of Syria. He told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on Tuesday: “It may be too late to keep it as a whole Syria if it is much longer” before a settlement is reached.

Sure, partitions can be a solution to intractable civil wars, as Chaim Kaufmann has made a career out of arguing, if policymakers are willing to pay the moral costs of what can amount to officially endorsed ethnic cleansing in order to create essentially homogenous, defensible enclaves.

But partitions can also lead to horrific bloodshed and human suffering (India-Pakistan 1947), decades of instability and recurring bouts of brutal violence (Ireland 1921), frozen front lines and fragile stalemates (Bosnia 1993), or refocused civil war and headlong descent to failed-state status (Sudan-South Sudan 2011).

The fate of Kurdish, or Sunni, or Shia, or other minorities left behind redrawn ethno-religious lines is an uncomfortable detail that advocates of partitionist solutions have to close their eyes to in the name of a solution to the larger conflict. Likewise the fate of Syrians of any persuasion who would face the misfortune of finding themselves in territory ceded to ISIS control.

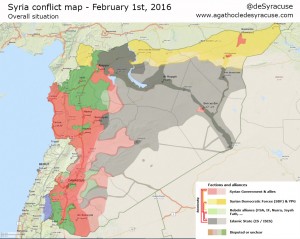

And then there is the really hard question: Exactly what would a partition of Syria look like? Consider this map of the country as of the first of February. You tell me what a viable, and therefore stable, partition of the country would look like. What do you do with regime forces and their allies surrounded by Kurds in the northeast? Or the Kurds cutoff and isolated in the northwest? Or various opposition enclaves that dot the map like holes in Swiss cheese? Or the huge swath of ISIS-controlled territory? And does the Assad regime get to retain the areas under its control, including Damascus?

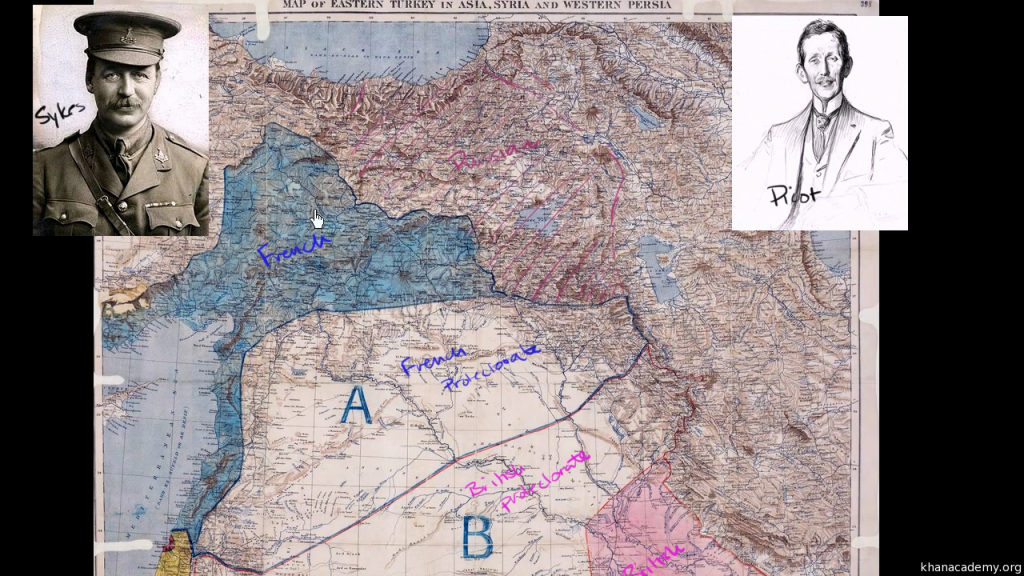

In a very real sense, the violence now tearing apart Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and elsewhere in the Middle East is a consequence of foreigners drawing lines on maps and calling things settled. Like the Sykes-Picot agreement, reached in secret between Britain and France in 1916 with the assent of Russia, which bequeathed to us the modern map of the region and with it sowed the seeds of future conflict. ISIS has vowed to erase it.

Is Kerry serious about redrawing the borders of Syria? Hard to say. As Joshua Keating points out at Slate, this isn’t 1919 and Kerry isn’t Sir Mark Sykes.

Then again, if Plan A works, then we’ll never have to worry about what might or might not constitute Plan B. Let’s hope Plan A works then.