While we were distracted earlier this week by the Michael Cohen show on Capitol Hill and the failed Trump-Kim love fest in Hanoi, two nuclear-armed rivals tiptoed up to the brink of war and then … stepped back.

On Tuesday, India launched airstrikes into Pakistan, targeting a training camp belonging to the terrorist group Jaish-e-Mohammed, in retaliation for a suicide bombing on Feb. 14 that killed 40 Indian soldiers on the outskirts of the city of Srinagar, in the Indian-controlled territory of Kashmir. JeM is a Kashmiri separatist group sponsored by the Pakistani government.

A day later, Pakistani jets crossed into Indian territory, then shot down at least one of the Indian fighters that scrambled in pursuit. The pilot was captured by Pakistani forces. Amid all this, news reports indicated that both sides had activated and reinforced their heavy armor formations along the Line of Control that separates Indian from Pakistani-controlled Kashmir. Troops exchanged fire across the border.

By Thursday, leaders on both sides began to acknowledge just how much danger everyone was in:

Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan said in a televised address that the two sides could not afford a miscalculation “given the weapons we have”.

“We should sit down and talk,” he said.

“If we let it happen, it will remain neither in my nor [Indian Prime Minister] Narendra Modi’s control.

“Our action is just to let them know that just like they intruded into our territory, we are also capable of going into their territory,” he added.

Indian Foreign Minister Sushma Swaraj also said “India does not wish to see further escalation of the situation.”

Today, Pakistan handed their captured Indian pilot over to his own government. The crisis seems to have abated.

So what does this episode tell us? It might tell us that nuclear deterrence actually works.

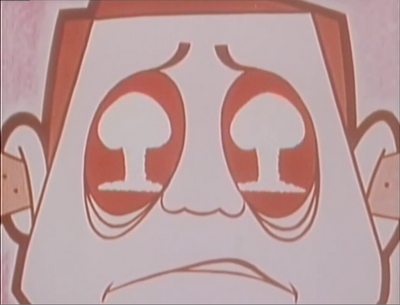

India and Pakistan each have about 140 nuclear weapons that can be delivered by short or medium-range missiles, cruise missiles, or aircraft. Both are working to develop submarine launched nuclear missile systems. Both countries’ nuclear doctrines emphasize deterrence, promising to deliver an unacceptable level of punishment against anyone that dares attack.

Forty years ago, political scientist Kenneth Waltz argued that nuclear arsenals like these would have the desired effect of forcing caution on states that might otherwise be tempted to escalate a crisis like this week’s between India and Pakistan to full scale war. I wrote about this a month ago in the context of discussing North Korea’s nuclear weapons program.

Given the catastrophic damage that nuclear weapons can inflict, even if used in relatively small numbers, Waltz writes that nuclear weapons make “both sides more cautions and the tensions between them less likely to lead to anything more than a skirmish.” Miscalculation, which Waltz rightly says has historically been an important precipitant of war, become less likely under such conditions due to the disastrous consequences of getting it wrong.

Put it all together, and nuclear-armed rivals like India and Pakistan have every reason to quickly de-escalate any crisis that threatens to get out of hand. India and Pakistan have fought three major wars since each won independence from Britain in 1947, two of them over the disputed territory of Kashmir. But since both became nuclear weapons states, their clashes, while troubling, have stayed contained.

When my students read Waltz’s arguments on the virtues of nuclear weapons, they often come away doubting the logic. And it stands to reason. Our human sensibility argues strongly that the last thing we should want is to see more of these weapons in the world. And yet, we have to acknowledge the reality that nuclear weapons, so far, have only been used in anger once. By us. Before any other countries had these weapons.

More nuclear weapons in the hands of more countries has not led to more use of nuclear weapons. So maybe Kenneth Waltz was right. Maybe nuclear proliferation is good.