For most Americans, near as I can tell, it’s not what the guy pictured above did. He’s Wade Michael Page, and four years ago he gunned down six worshippers at a Sikh temple in Oak Creek, Wis., before before being killed by a local police officer.

Page, a veteran of the US Army, had spent decades swimming in the deep end of the cesspool that is the white supremacist universe. He was a member of two white power skinhead bands, End Apathy and Definite Hate. In 2010 End Apathy played at a racist music festival in Baltimore called Independent Artist Uprise.

Page literally wore his sympathies on his sleeve in the form of a tattoo, “14 Words,” a reference to a slogan coined by David Lane, a member of a notorious violent white supremacist group called The Order. Lane died in prison in 2007.

These are the 14 Words:

We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children.

Page’s deadly attack on the Sikh temple on Aug. 5, 2012, was one of three acts of domestic terrorism between mid-July and early August of that year. And yet, when polled by Gallup only a week later, fewer than 0.05 percent of respondents reported that they considered terrorism the most important problem facing the nation.

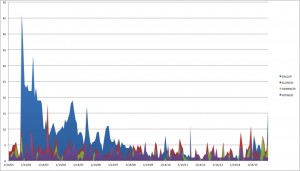

I know this because I am currently working on a research project with a student of mine trying to understand what drives American public opinion on the significance of terrorism as a public policy problem. Click on the graph to take a very preliminary look at the data.

I know this because I am currently working on a research project with a student of mine trying to understand what drives American public opinion on the significance of terrorism as a public policy problem. Click on the graph to take a very preliminary look at the data.

Our operating assumption is that opinion reacts to terrorist incidents, both attacks inside the United States and attacks abroad targeting American citizens or American facilities. And yet as we look at the data, the patterns of correlation, let alone causation, are far from clear cut. In short, the American public reacts to some incidents but not others.

Here’s another example. In June 2015 Dylann Roof, another white supremacist, shot to death nine black churchgoers at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, S.C. In the Gallup poll a few weeks later, the percentage of Americans reporting that they considered terrorism the most important problem facing the country fell by two points to 3 percent from the prior month, one in which there were no incidents of domestic terrorism, only a single international attack in which no Americans were either killed or injured.

Jump forward six months, though, to early December and San Bernardino, Calif. Here a husband and wife team, after she declared allegiance to ISIS, killed 14 people and wounded 21 at a holiday party at the government offices where he worked as a county health inspector.

In the Gallup poll conducted several days later, a full 16 percent of the American public declared terrorism the most important problem facing the country, up from only 3 percent the prior month. Likewise, after the Boston Marathon bombing in 2013, another case in which the perpetrators were motivated by jihadist sympathies, the percentage of Americans declaring terrorism the most important problem more than doubled.

While we haven’t yet done any of the fancy math to try to figure out the actual causal relationships between terrorism incidents and the salience of terrorism for the American public, the anecdotal evidence implies that much of what scholars classify as terrorism — events like Oak Park and Charleston — doesn’t fit the public’s post-9/11 conception of what terrorism is.

San Bernardino and Boston — where “they” commit acts of horrific violence against “us” — are terrorism. Oak Park and Charleston — where we commit acts of horrific violence against each other — are something else entirely.

And yet they’re not. This reality was driven home yet again by a report Friday night out of Kansas. The FBI disrupted a plot by a militia group called the Crusaders to detonate a series of simultaneous car bombs at an apartment complex and mosque where Somali immigrants live and worship:

[T]he men were stockpiling weapons and were going to publish a manifesto after the bombing, which was occur Nov. 9 so as to not affect the general election.

One of the men said that the bombing “would quote, ‘wake people up,’” Beall said.

They formed a plan of violent attack targeting Somalis and — after considering a host of targets, including pro-Somali churches and public officials — settled on the apartment complex. Some residents of the complex maintained an apartment that served as a mosque, he said.

The plot involved obtaining four vehicles and filling them with explosives. The men discussed parking the vehicles at the four corners of the complex and detonating them.