In April, the New Jersey Office of Homeland Security released a report on domestic terrorism in the United States during 2018. They documented 32 terrorist attacks, disrupted plots, threats of violence, or weapons stockpiling by individuals motivated by a radical social or political agenda and who had not been influenced or directed by any foreign terrorist organization or movement.

All 32 cases were driven by far-right political or social ideologies. Thirteen of the 32 were perpetrated by race-based extremists, another 17 by right-wing anti-government extremists. African-Americans were targeted in 29 percent of all incidents, Jews in another 10 percent. Nineteen percent of incidents targeted law enforcement.

In short, what the NJOHS reported in April is perfectly consistent with what I have been asserting for nearly all of the four years that I’ve been writing this blog. The primary threat of terrorism in the United States comes not from wild-eyed jihadists but from the ranks of America’s anti-government and racist far right.

But lest we think this is some kind of recent development, a new dataset on terrorist organizations that formed between 1860-1969, compiled by University of Iowa Ph.D candidate Joshua Tschantret, reminds us that this is nothing new at all. It is, rather, the historical norm.

According to Tschantret’s data, 28 terrorist groups formed and were active in the United States between 1860 and 1969. Of those 28, nearly half, some 13 organizations, carried out acts of violence, including bombings and assassinations, in support of right-wing ideologies. All but one of these were motivated by white supremacist ideology. The lone exception was the Secret Army Organization, formed in California in 1969 and targeting the organizers of anti-Vietnam War demonstrations. All of the rest used violence in pursuit of explicitly racist goals.

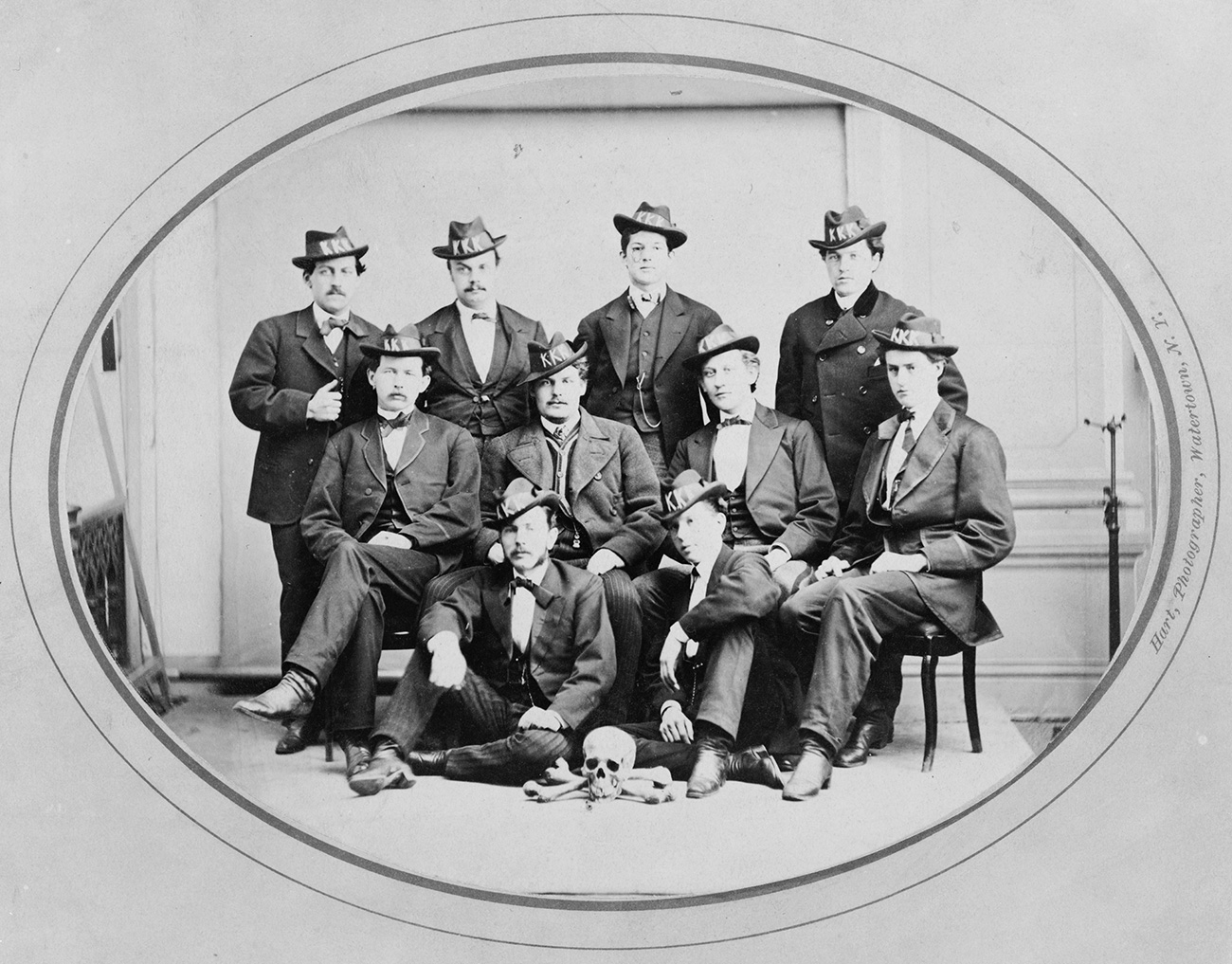

The earliest of these groups came together in the South during the early years of Reconstruction, in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, groups like the original iteration of the Ku Klux Klan, and others such as the Southern Cross and the Knights of the White Camellia. The White Line would spring up a decade later, in 1874 in Mississippi, and the Klan would be reborn in Atlanta in 1915. A decade later would come the Black Legion, a Klan splinter group organized in Bellaire, Ohio by a doctor named William Shephard.

Atlanta would also see, in 1946, the emergence of the Columbians, a racist and anti-Semitic pro-Nazi organization. Edward Folliard of the Washington Post would win a Pulitzer Prize in 1947 for his reporting on the group. The 1950s would bring yet another rebirth of the Klan, this one still in existence today, along with more offshoots, like the Original Ku Klux Klan of the Confederacy, born in 1955 in Birmingham, Ala., followed by the United Klans of America in 1960.

The 1960s would spawn two more white supremacist organizations. The Silver Dollar Group emerges in Louisiana in 1964 as a Klan offshoot organizing in leaderless resistance cells which assassinated African-Americans and bombed the cars of NAACP organizers. The White Knights of Mississippi, another Klan branch, also organized in 1964 and continues in existence today.

The definitions of terrorism that scholars like me adopt when we study and teach about this phenomenon tend to point to 1860 as the birth of the modern era of terrorism. That brings us face to face with a sad but inevitable conclusion:

Our past history of racist, right-wing terrorism in America is consistent with our present reality of racist, right-wing terrorism in America. El Paso is just the bloodiest, most recent example.