Note — This post is by Dominic Mier, a student in the Honors College at Oakland University majoring in Bioengineering. Over the next few months, students in my course, International Relations on Film, will be contributing posts to the blog reflecting on the movies we are watching in class and the ideas those films are helping us to think about. Dominic’s piece is presented here with minor editing.

Americans have always loved Western movies. We love the way the hero is glorified, always prevailing against the evil gunslinger he quarrels with. The good, honorable hero always wins the gunfight. His town celebrates him, cheering and praising him. He defends what’s right and just. He represents how Americans see their nation.

Then you have a film like High Noon, directed by Fred Zinnemann and premiered in 1952. On the surface it’s a typical Western where the good marshal kills the criminals who’ve returned to his town years after he after once drove them out. But as you examine this film on a more critical level, it becomes clear that High Noon is more than a film about good versus evil. Perhaps it was the story of the screenwriter, Carl Foreman.

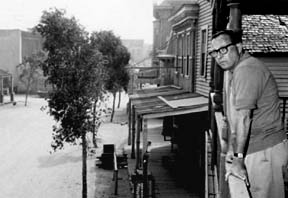

Despite being an acclaimed film producer and screenwriter of such classics as Bridge on the River Kwai and The Guns of Navarone, Foreman was blacklisted in 1951.

At the height of the Cold War in the early 1950s, the fear of communism had spread through the United States like wildfire. The House of Representatives had formed the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) in 1948 to investigate government employees and the film industry, a year after President Truman issued the Loyalty Act, requiring all federal employees to be investigated. A senator from Wisconsin, Joseph McCarthy, made it his personal crusade to go after these individuals.

McCarthy would accuse individuals who disagreed with him of being communists, effectively ruining their careers. A “blacklist” spread throughout Hollywood, filled with names of suspect actors, actresses, directors, writers, even crewmen who weren’t to be hired because of their supposed communist associations or sympathies.

Carl Foreman was one such man. He found himself targeted by McCarthy and blacklisted, unable to work in Hollywood. He was brought before HUAC in 1951, where it was revealed he had been a member of the American Communist Party several years earlier but had since cut ties. He refused to expose other members, and was hence blacklisted. He left the U.S. and fled to Britain. Though he continued work in the film industry, Foreman did not return to the U.S. until later in life.

The plot of High Noon seems to be much the same as Foreman’s own story. Will Kane (Gary Cooper), the marshal in the film, is haunted by his past coming back around. Frank Miller (Ian MacDonald), a gunslinger, comes back to town after Kane sent him to the north to be hanged. Like Kane, Foreman was haunted by his own banished past.

Kane searched the town he had protected for so long for deputies and found none would join him. The mayor told him it was his problem to deal with. His deputy quit. His friends hid from him. Even his own wife threatened to leave him. Kane was alone, much like Foreman must have felt.

No studio executives would work with him anymore; they were mid-production of High Noon when Foreman was hauled before HUAC. Foreman had nothing left, his career in Hollywood was ruined. He was forced to leave the country and continue in Britain.

In High Noon Kane overcomes the odds and defeats Miller and his gang with the last minute help of Amy (Grace Kelly), his pacifist wife, who guns down a man in order to save him. Perhaps referencing that if someone had stood up for him, Foreman may have defeated his own past.

The Old West is a classic example of a land ruled by anarchy. The lawmen were spread across a huge expanse, days away in some instances. This was a land where men took care of their issues as Kane did, with guns and violence. No one man ruled for longer than another man wished.

Foreman felt his situation was the same. Citizens no longer had rights. It was one man’s word against another’s. The government was on a wild goose chase, ruining lives of anyone suspected of communism.

This was a rough time in history for American citizens. Japanese-Americans had been imprisoned in internment camps just a few years before. Communists were feared to have infiltrated the country and its government. The civil rights movement was in its infancy, beginning to protest the treatment of African Americans.

In short, it resembled the anarchic times of the Old West, and Foreman saw a need to call attention to that. High Noon, then, is less a typical Western film, and more of an outcry against the government’s treatment of its own citizens.