I’m going to warn you now, this post is even more esoteric than usual. But it is a diversion from the usual seriousness on display here, so bear with me.

I want to introduce you to a very old and now rare American tradition with roots in Scotland, still practiced by church communities in places like Alabama, Kentucky, and Oklahoma who are bound together by shared faith and musical inheritance.

It’s called lined-out hymn singing, a call-and-response form of sacred song whose roots in this country can be traced to the Scots tradition of a cappella Gaelic psalm singing which can still be heard in the remote and isolated communities of Scotland’s Outer Hebrides, especially the Isle of Lewis.

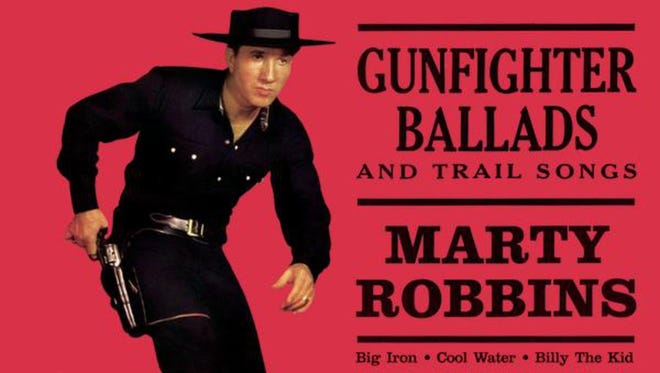

It is a precursor to the obscure form of group a cappella singing that I do, shape-note singing from a hymnal called The Sacred Harp. I’ve written about this before in this space.

It is frankly hard to describe the sound of lined-out singing. It is haunting and raw, almost primitive in its intensity. This is literal hair-standing-up-on-the-back-of-your-neck music.

I have never heard it in person, though some of the folk that I sing with when I travel to Alabama for Sacred Harp singings (back in nearly forgotten pre-pandemic times when such things were still possible) also sing lined-out hymns or psalms. Apparently if you’ve seen the Loretta Lynn biopic Coal Miner’s Daughter, you can find lining-out depicted at her father’s funeral.

Apparently the music, once common in 17th and 18th century Britain and America, fell victim to disputes about what music was appropriately edifying for singing in church. You can dig deeper into the “controversy” as it played out in Puritan New England here.

I’ve only experienced this tradition through recordings and videos found on YouTube. But it turns out that there is a fantastic short documentary from Yale University that digs deep into the music and the communities that still sing it – Hebridean islanders, a Black congregation from Alabama, a White congregation from Kentucky, and a Muskogee Creek congregation from Oklahoma who brought the music west with them on the Trail of Tears.

The documentary is called “A Conjoining of Ancient Song,” and you can watch it below. Here’s the introduction to the film, posted at Vimeo:

A special Yale documentary retraces the trajectory of a rapidly eroding form of congregational singing out of Scotland and into African American, Native American, and white American religious song traditions. The Yale Institute of Sacred Music, one of the film’s sponsors, organized a first screening at the University in April 2013, and offers it to the public here.

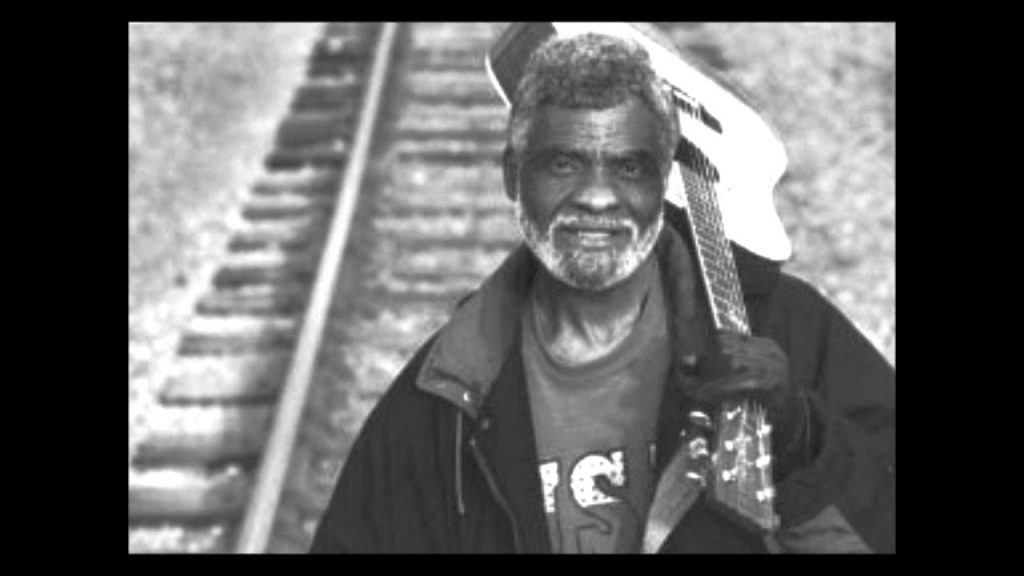

The renowned jazz musician and ethnomusicologist Willie Ruff began his journey began several years ago, when he followed up on his friend Dizzy Gillespie’s claim that some remote African American congregations in the Deep South sang hymns in Gaelic, according to Ruff’s website. Consulting The Massachusetts Bay Colony Psalm Book from 1640 in Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, he found that the form, in which one church member calls out the first line of a Psalm and the rest of the congregation continues to chant the text in unison, had been a common worship practice in Colonial America. Pursuing the inquiry, Ruff made the startling discovery that this call-and-response service, chanted by descendants of African slaves in the American South and by white congregations in remote churches of Appalachia, was actually still intoned in Gaelic in its original form in Scotland’s remote and culturally isolated Outer Hebrides.

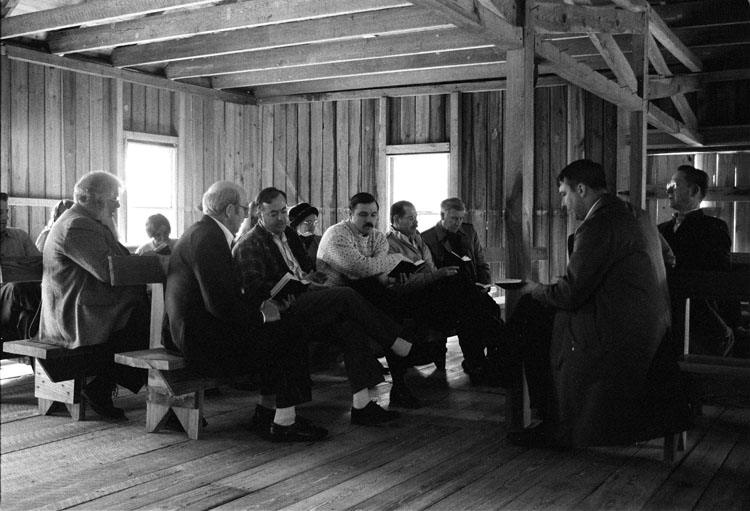

In 2005, he organized an international conference at Yale, bringing together a few of the almost extinct congregations still practicing the ancient line-singing tradition. The Free Church Psalm Singers of the Isle of Lewis, Scotland; the Indian Bottom Old Regular Baptists of southeastern Kentucky; and the Sipsey River Primitive Baptist Association of Eutaw, Alabama, came to perform a shared service that had adapted over generations to their diverse idioms. In the course of that conference, he learned that the tradition extended to the Muskogee Creeks in Oklahoma as well, and two years later, Ruff, who traces his own lineage back to the crossroads of races and cultures represented in the unusual custom, organized a second conference at Yale to gather Native American, African American and Appalachian line-singers together for the first time.

The 30-minute documentary “A Conjoining of Ancient Song” is the story of Willie Ruff’s journey connecting Gaelic psalm singing and American Music.

It is a wonderful film, with haunting music and profound emotion. The academics are, at times, well, too academic. But the real people who sing this music, and the connections they have with each other, bonds of faith, fellowship, and tradition, are deeply touching.