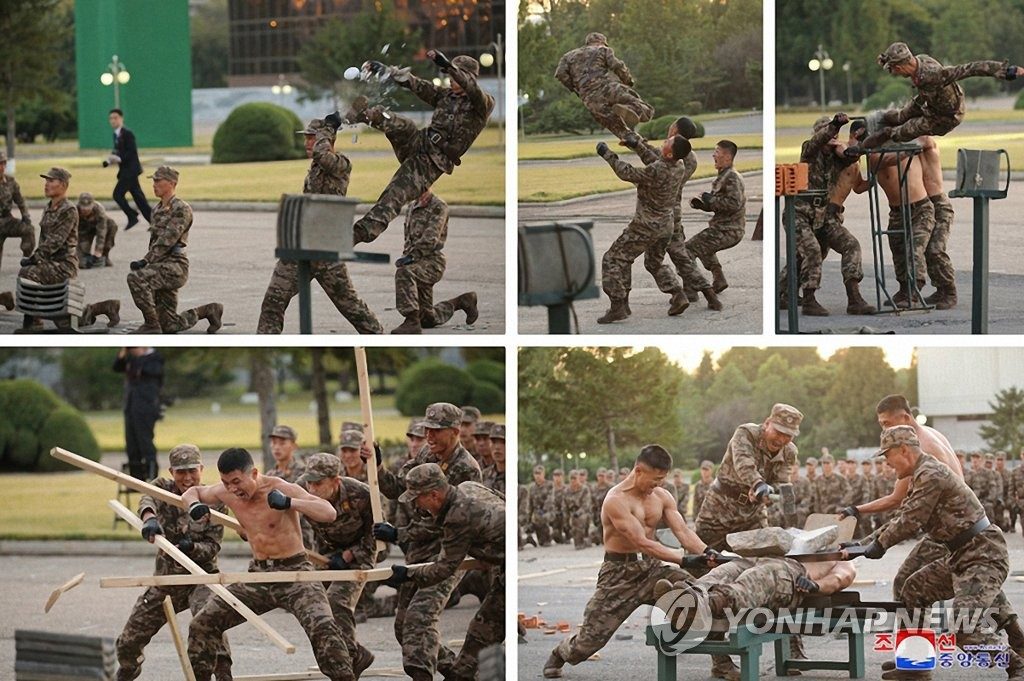

North Korea wins the bricks and sticks war hands down.

North Korea wins the bricks and sticks war hands down.

This demonstration at the Defence Development Exhibition was bit intense. Video broadcast today on North Korean TV. pic.twitter.com/zehpI6EAEd

— Martyn Williams (@martyn_williams) October 12, 2021

In his belated State of the Union address last week, President Trump had this to say about North Korea:

As part of a bold new diplomacy, we continue our historic push for peace on the Korean Peninsula. Our hostages have come home, nuclear testing has stopped, and there has not been a missile launch in 15 months. If I had not been elected President of the United States, we would right now, in my opinion, be in a major war with North Korea with potentially millions of people killed. Much work remains to be done, but my relationship with Kim Jong Un is a good one.

I think Trump has the kernel of a valid point here. The situation on the Korean Peninsula was much more dangerous before he came into office than it is today. The situation is more stable, and thus a lot safer, now. The president is just wrong about why.

Trump ascribes this new stability to his self-professed superior deal-making skills and his “we fell in love” relationship with North Korea’s brutal dictator Kim Jong Un. Let me suggest a far more plausible explanation.

The Korean Peninsula is more stable today not because of Trump’s brilliance, but because North Korea has perfected its nuclear capability and clearly demonstrated its ability to deliver a warhead on American soil. In November 2017, following the “fire and fury” summer of escalating threats and counter-threats, North Korea successfully launched the Hwasong-15 intercontinental ballistic missile with an estimated range of more than 8,000 miles, enough to hit any target in the continental United States.

They haven’t tested a missile since. Because. They. Don’t. Have. To.

Having proven that it can put a nuke on a mainland American target, North Korea no longer needs to test its missiles or the weapons themselves. The lull that Trump is taking credit for has nothing to do with him, and everything to do with the maturity of North Korea’s nuclear weapon and ballistic missile programs.

In 1979, in an essay prepared for a joint CIA/Department of Defense conference, political scientist Kenneth Waltz argued that the gradual spread of nuclear weapons was, contrary to the fears of public and policymakers alike, a force for increased stability in the international system, and would therefore produce a safer, not more dangerous, world. (You can read Waltz’s further elaboration on this idea here.)

Waltz argued that nuclear weapons, because their effects are so catastrophic, make states more cautious and less willing to take risks that could lead to an escalation and nuclear exchange. Under these conditions miscalculation, historically a significant contributor to the outbreak of war, becomes less likely because getting it wrong has such dire consequences.

In short, once nukes are introduced into the equation, no one can play fast and loose with the kinds of aggressive actions that risk provoking a nuclear holocaust.

Apply these ideas to the relationship today between the United States and North Korea and you can understand why the Korean Peninsula is more stable, and thus safer, than it was in 2016. Until last year, the nuclear equation was one sided.

The United States could bluster and threaten a preemptive strike against North Korean targets secure in the knowledge that any retaliation by the North would fall on South Korea or maybe Japan. Yes, hundreds of thousands of civilians would die, but those wouldn’t be American cities burning. Seoul or Tokyo aren’t Seattle or San Francisco. That might be the kind of loss an American president could be willing to accept.

That option is now off the table. And that’s the reason why North Korea will never denuclearize, as President Trump’s own intelligence chiefs have testified, contradicting their boss.

North Korea now possesses a nuclear deterrent sufficient to force the United States into a more cautious, less risky, posture toward the Kim regime, just as the American nuclear monopoly induced the same kind of caution on part of the North Koreans.

The Korean Peninsula is safer and more stable today because North Korea achieved nuclear maturity on Donald Trump’s watch. That’s a good thing, but hardly the story the president wants to tell.

So, Trump didn’t lose the farm in Singapore yesterday, but he did leave the summit with North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un a few prize cows short.

When I wrote about the Trump-Kim summit last month, it was on the heels of the news that Trump had backed out of the planned meeting after raising impossible-to-meet expectations of what he could accomplish. Having dealt himself an incredibly weak hand, Trump announced he would walk.

And then he came slinking back to the table just eight days later, having discarded demands for rapid North Korean denuclearization and relaxing the US posture of “maximum pressure” on the Kim regime. With expectations lowered to, in the president’s own words, a more modest “getting-to-know-you meeting, plus,” the summit was back on.

Now that it’s over, how what did the meeting produce? Let’s just say that Donald Trump, self-proclaimed master negotiator and deal maker, gave away a lot more than he got. Actually, that doesn’t quite capture it. Trump made all the concessions and got nothing new in return. Let’s break it down:

What did Trump get in exchange for all of these giveaways? A joint communique repeating the vague pledge to “work toward complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula” which had been made back in April. That, and a stated desire to work toward warmer relations. And that’s all.

No clarification of what each side means by denuclearization. No mention of timetables for moving forward. No mention of verification.

And not a single concession from Kim Jong Un. In fact nearly identical pledges were made by the North Korean regime back in 2005 and 1993. You see how closely those were honored.

Don’t get me wrong, granting unilateral concessions to your counterpart is an absolutely legitimate negotiating strategy, especially if the intention is to build goodwill and trust that will lead, down to road, to the other side reciprocating with some compromises of its own. But nothing in the long history of US-North Korea diplomacy leads me to believe such compromise will be forthcoming.

So in the end, all Donald Trump may have achieved in Singapore was a dramatic photo op. Of course, maybe that’s what he really wanted.

In what may be the least surprising development in Trump-era foreign policy, the president has backed out of his upcoming summit with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un.

Having impulsively agreed to meet with North Korean dictator, without preconditions, raising ridiculously high expectations for the outcome by giving in to his habitual hucksterism, declaring himself a shoe-in for the Nobel Peace Prize, then making impossible-to-meet demands on the Kim regime while offering no concessions, this was probably inevitable.

As I told the host of a local news radio program more than a week ago, I would believe the summit was going to happen when I saw the two leaders sitting down at the table together. Now the big question is what will the Trump administration going to do with all those commemorative coins they had made?

As I told the host of a local news radio program more than a week ago, I would believe the summit was going to happen when I saw the two leaders sitting down at the table together. Now the big question is what will the Trump administration going to do with all those commemorative coins they had made?

The United States was never going to get from the North Koreans what we said we wanted: immediate, complete, and independently verifiable denuclearization. And we had already gone a long way toward giving the Kim regime what it has long sought: Recognition as nuclear equals. That it has also forged closer ties with a South Korea spooked by the beating of war drums in Washington is just gravy.

When I teach negotiation, one of the cardinal rules I try to convey to my students is the need for negotiators to always have an eye on what’s called their “BATNA” — their best alternative to a negotiated agreement. It’s a simple idea. If any deal you could get would constitute a worse outcome then what happens if you walk away from the table, then you should walk. Even at the cost of what looks and feels like humiliation.

I wrote in this space last week that President Trump, due to all of those points raised at the top of this post, and more, had dealt himself an impossibly bad hand to play in a diplomatic game with incredibly high stakes. So rather than play out the hand, Trump did the only thing he could.

Having carelessly built the pot while holding a losing hand, he folded.

We’ll have to wait to see if that really was the best alternative.